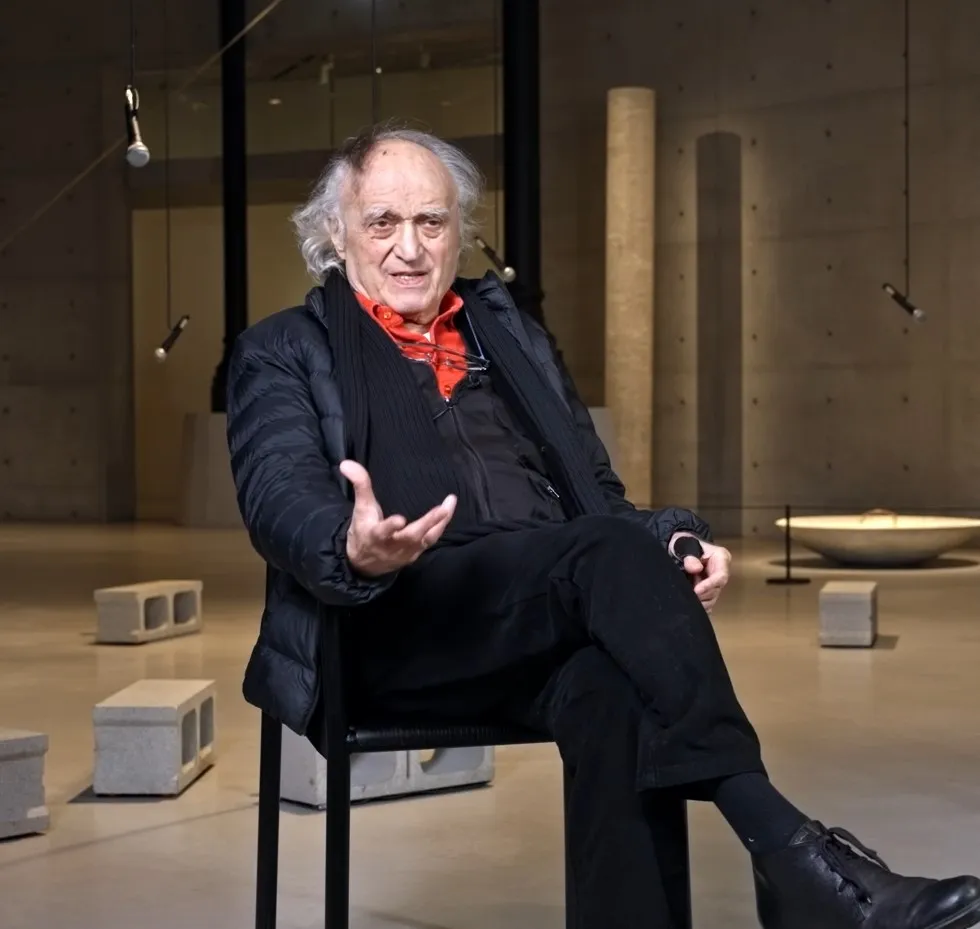

“My work is an exploration” — Gilberto Zorio

A historic figure of the Arte Povera movement, Gilberto Zorio shares his thoughts on art and talks about his works on exhibit until 20 January in the Foyer of the Bourse de Commerce.

Your works engage chemical and physical phenomena. Why are you interested in energy?

I have always thought that an artwork exists in a state of perpetual transformation. I like to imagine it over time, wondering what it will be like tomorrow, in a year, and so on, because there is always a slight transformation.

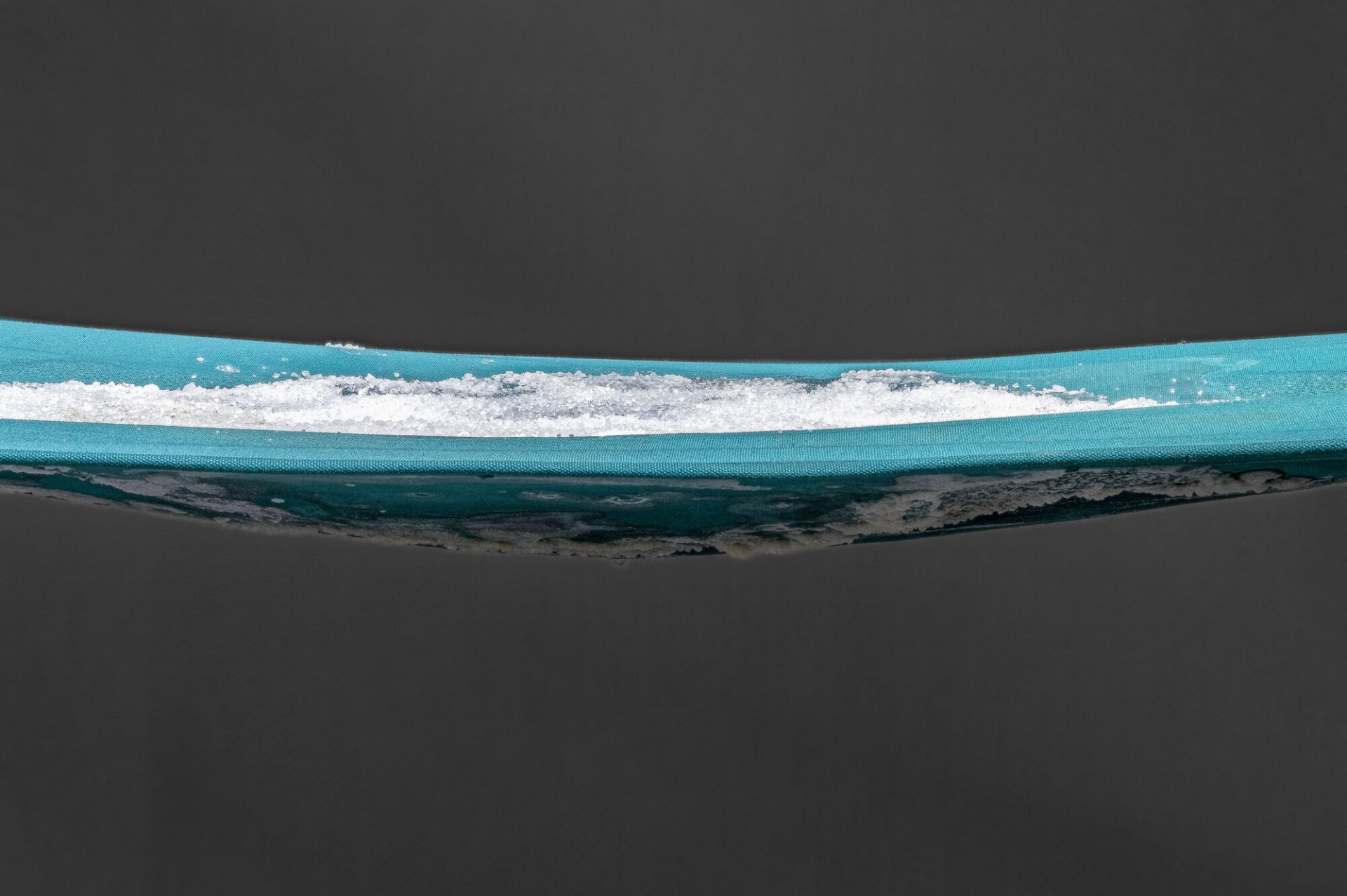

My work Tenda (“Tent”) (1967) is the result of a marvellous shock I once experienced at a campground in Liguria. A storm had “lifted” the sea and all the tents next to mine blew away. The following day, the entire campground was covered in salt from the saltwater that was rising up through the ground. That provoked tremendous emotions in me. So, when I went back to Turin, I bought two green and blue canvases, and I fabricated a kind of “memory”.

“An artwork exists in a state of perpetual transformation”

In Odio (1969), you use the energy of anger. Do you think of emotions as materials?

“Odio” (which means “I hate”) is a terrible term that also means “evil”. In my piece Odio, the vegetal component – the rope encrusted in the metal – holds the weight of the lead plaque on which the word “odio” is written. This weight is very heavy, but the union of the plants that form the rope is even stronger. It is an almost Christian vision of good and evil.

Can you tell us about your piece Microfoni (1968)?

In this work, concrete blocks are arranged on the ground that visitors can use to step up to the height of the microphones and speak. For me, it is as if we alziamo verso un piccolissimo cielo (we rise towards a tiny sky). Sound, the repetition of words, signify memory. The incredible thing is that, when we talk and the sound comes back to us, we judge ourselves immediately. We then adapt how we speak, we talk about ourselves differently, we play, we sing, we swear, we say “psycho-pseudo-erotic” words. It’s interesting to hear what people say.

The work Rosa-blu-rosa (“Pink-blue-pink”) in the Rotunda can change colour over the course of the day. Can you tell us how it does this?

At the time, I was in the habit of using concrete, which has a neutral structure. This is true of Rosa-blu-rosa, currently on show in the Rotunda, which consists of a half-cylinder of reinforced concrete. The mixture with cobalt chloride on the inside renders the work unstable and turns the pink to blue. It moves over time, with the climate. It becomes sensitive and it evolves in silence.

I exhibited this piece on 14 November 1967 at Sperone, a gallery in downtown Turin. It snowed a lot that evening. The artist Lucio Fontana walked into the gallery, and with the contrast between the humidity outside and the heat inside, the blue in Rosa-blu-rosa became pink. When we explained this phenomenon to Fontana, he said, jokingly, “It’s like my mood, always changing”.

Several of your works demarcate spaces, boundaries. Can you explain this for us?

I created Macchia (“Spot”) in 1968 in Turin. Usually we see spots on the ground, but in this case, I instead imagined a spot in the sky. I suspended it mid-air.

The work Confine is from a different period. It is more political. The title Confine (“border”) represents the imaginary line that arises through violence. If you open a geography book, you can see that, especially in Africa, vertical and horizontal lines were drawn arbitrarily. That’s the Confine, the border. It was very violent. We deported people. We did terrible things. And it was an interpretation of religion in particular that engendered these crimes. I then thought of heating this wire to 1,000 degrees for the nickel chrome to become very hot. And you don’t forget the word Confine. When you stand next to it, you feel the heat. Heat is magnificent, but it’s also very dangerous.

In the Machine Room, you installed two works that work using Wood lamps. They have two states: one under normal light, and the other, black light. What was the reason for this choice?

I am interested in revelation. This lets you see things that you normally can’t. For example, the police uses Wood lamps to check for traces. Phosphorous comes from the Ancient Greek phôsphoros, which means the “carrier of memory”. For me, the fist you see in this room does not represent violence; it is merely the concentration of the power of memory. I tighten my fist, and I preserve my memory, which is instead cast off when the light goes out.

The other piece, È Utopia (“It’s Utopia”) uses fluorescence. The invisible becomes visible. It will complete the following sentence: È Utopia, la realtà, é rivelazione (“Reality is a utopia, is a revelation”). Reality is a revelation, which is the exact opposite.

What does Arte Povera mean to you?

Someone said that Arte Povera was a question of futurism. I don’t think this is true. For me, Arte Povera is about inventing surprise, about what is surprising and will always be surprising. And I feel that this is still true today. This large exhibition at the Bourse de Commerce is extraordinary, because the room featuring my works does not only elicit feelings from the past; when I walk through it, I am still in the process of searching and exploring. My work is an exploration.

The Arte Povera exhibition is open until 20 January 2025 at the Bourse de Commerce.