"Araki, whose heart exploded with love"

What is particularly remarkable about Araki’s entire visual œuvre [..] is the impression of a free play between the anecdotal or the everyday and the studied pose or composition, between, as it were, his real life and his “artistic life." Simon Baker

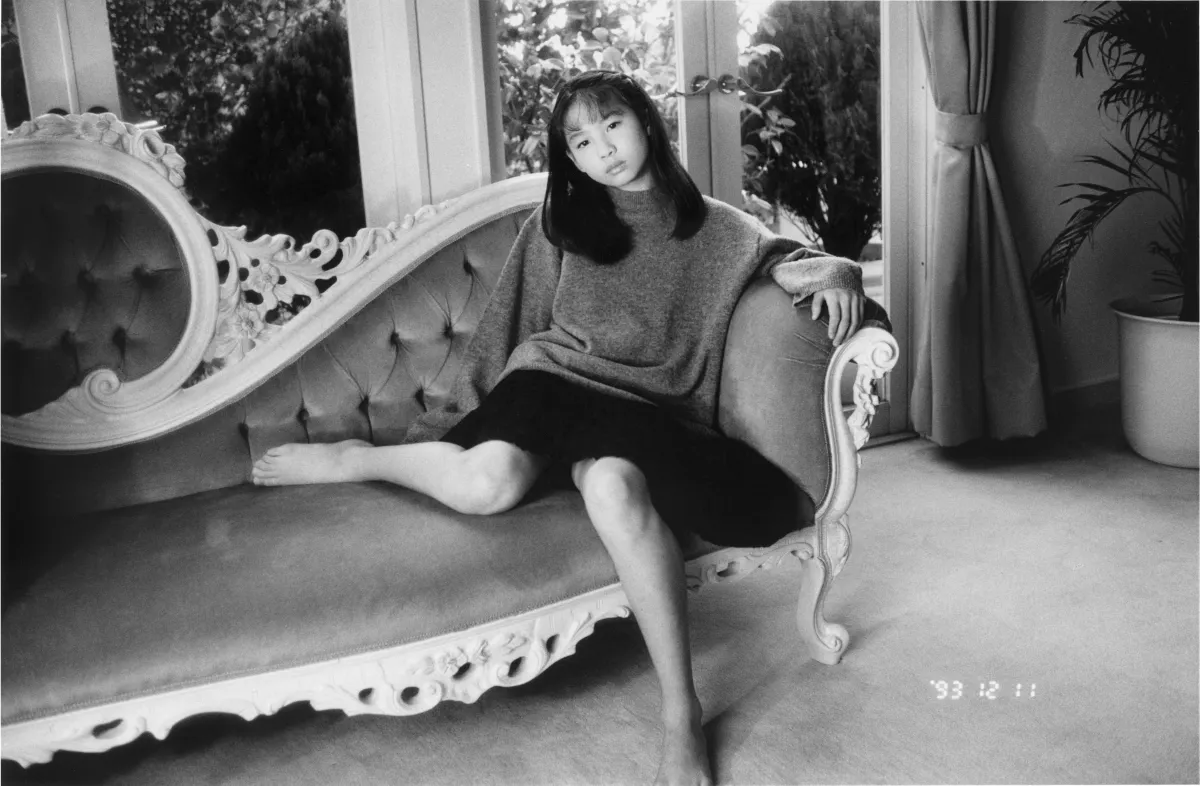

“A good translator would explain that when Araki says one thing, he is implying at least three others. These early works, which often take the form of diaries or “pseudo-reportages”, immerse us in the world and mind of one of Japan’s most extreme, manic, and creative photographers. What is particularly remarkable about Araki’s entire visual œuvre, as well as in his writings, and even more so in his long series Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank, is the impression of a free play between the anecdotal or the everyday and the studied pose or composition, between, as it were, his real life and his “artistic life”. Nowhere is this more at stake, more in question, than in his presumably insatiable appetite for photographing the female form, both in situations of presumed intimacy and of extreme and often explicit artifice. Araki, whose heart exploded with love for his wife Yoko to the point of compulsively documenting both the happiness of their honeymoon and the tragedy of her death, is also the photographer immediately associated with images of kinbaku, a traditional and highly ritualized form of Japanese bondage. Western orientalist logic, or external logic, often suggests that this kind of fetishism is inherent in the variable geometry of a seemingly impenetrable Japanese morality: perfectly polite, respectful of convention, and even prudish in public (or during the day), and conversely wildly transgressive in private (or at night). This moral relativism according to which Japanese audiences are more or less shocked by or open to Araki’s work does not, however, help us understand how or why he produces such images. Instead, we should pay attention to the photographs themselves—to their graphic composition, to their intense formal concern, to the narrative (or anti-narrative) logic of the seriality and order in which they appear. Araki incessantly returns to the same scenes, the same subjects and the same places: his neighbourhood, his cat, his collection of plastic dinosaurs, his favourite interiors, his bars, and his models. He once revealed that the first picture he takes every morning is an image of the sky from his balcony: “You brush your teeth, I wash my eyes.”

At first glance, Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank may seem like a deliberately incoherent work, a compilation of all sorts of things and places rather than a homogeneous series, but since it was created by an artist for whom even simple words have slippery meanings, it is perhaps more appropriate here to think of the set of images as another kind of pseudo-journal, a photographic exploration of the spaces between the real and all its potential opposites. In this context, it is useful to recall that it was Araki who coined (in Japanese) the term I-photography, a reference to the so-called I-novels, a Japanese literary genre based on confession that deliberately eliminated any sense of veracity by revealing and admitting things that, in fact, could also be carefully crafted fictions.”