About Luanda-Kinshasa

Since the end of the 1980s, through film, photography, and installation, Stan Douglas has explored the consequences of the reproducibility of images on the construction of the twentieth century political imaginary.

Since the end of the 1980s, through film, photography, and installation, Stan Douglas has explored the consequences of the reproducibility of images on the construction of the twentieth century political imaginary. By reinvesting the specifi-cities of narrative processes, his works form systems of reference crossed by social, historical, and cultural issues.

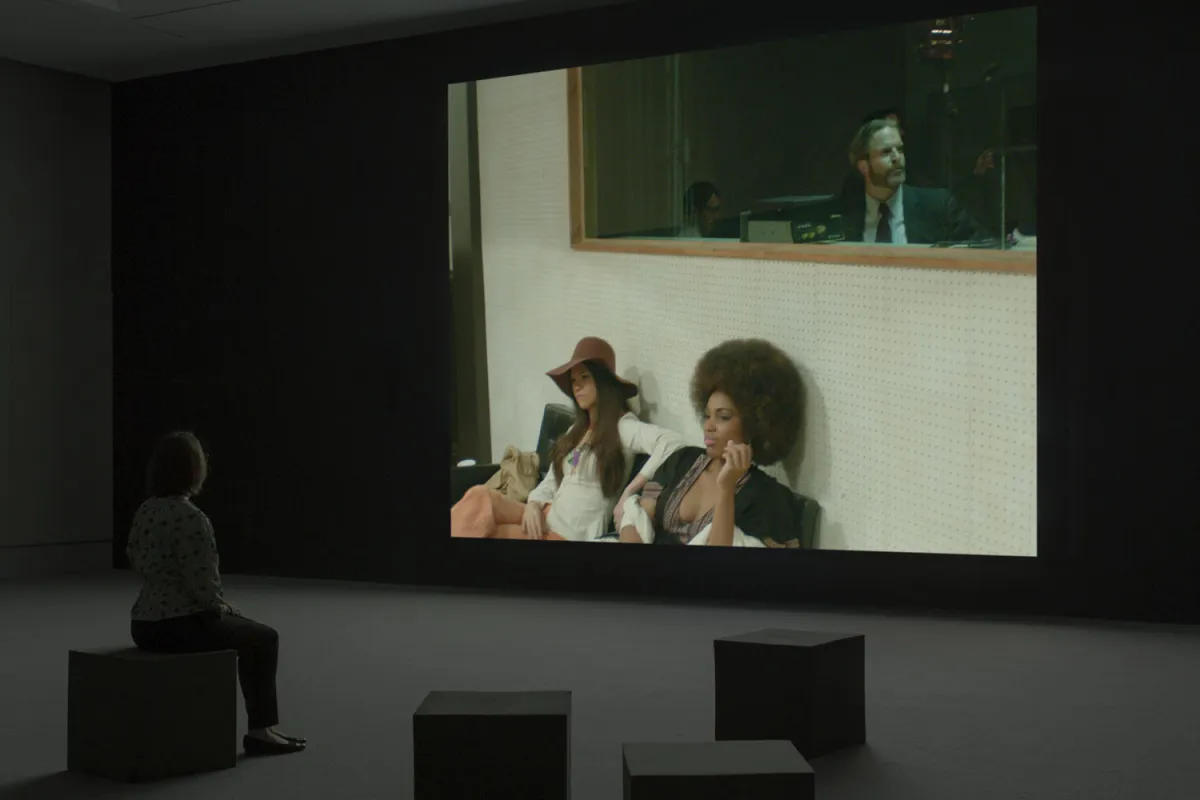

In his film Luanda-Kinshasa (2013), the Canadian artist stages a recording session during which ten musicians, gathered around the American pianist and composer Jason Moran, improvise two eponymous musical themes, Luanda and Kinshasa, drawing on the musical influences of jazz, funk, and Afrobeat. In a setting that offers the illusion of a bygone era and location, that of the legendary New York studio of Columbia Records—known as “The Church”—in the mid-1970s, the camera lens moves gradually, distinctly framing each element and character of the composition. Reconstructed for the film, this studio located in Manhattan in an abandoned Armenian church hosted, from 1948 to 1981, the greatest musicians and performers of the American music scene, including Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin. Witnessing this situation orchestrated by the artist, sound engineers, a photographer, and two grou-pies silently occupy the background to enhance the realism of the reconstruction. Connected to each other by headphones, the musicians appear separately on the screen, interacting with the other members of the group who are deliberately left out of the frame. The absence of an overall shot allowing us to view the scene in its entirety reinforces the sense of a fragmented visual composition which can only be experienced as a whole through the synchronization of the images and the soundtrack.

In the manner of a “palimpsest event,” as the artist puts it, Luanda-Kinshasa makes this moment of musical creation a fragmented reflection of the political and social context that conditions it. By placing the names of two African capitals side by side, the film’s title refers to the anti-colonial emancipation struggles and also to Pan-Africanism. In 1975, Luanda celebrated the liberation of Angola from Portuguese colonial rule, while Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) attrac-ted international attention by hosting the famous Rumble in the Jungle boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. Attentive to the way in which these historic events and their media coverage have influenced the development of the New York music scene, through this recording session Stan Douglas encapsulates the impli-cations of a hybridization between music, popular culture, and political history. In 1968, the filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard had opened up this path with his film on the Rolling Stones, One + One (distributed under the title Sympathy for the Devil) by showing the deep relationship between a popular musical genre and social and political protest. Adopting the genre of musical reportage that Godard had experimented with previously, Stan Douglas in turn favours a principle of observation and recording that appears to be linear and continuous. However, this effect of continuity of the performance on the screen turns out to be pure artifice: like a multi-track arrangement, the musicians’ contributions, recorded separately, were assembled at the time of editing. Composed of eleven sequences of similar length, the initial structure of the film is re-sequenced for the screen at the moment of the projection according to a system of permutations. Like a sound mix, this logic of reassembly exhausts the various possible combinations and converts the film into a series of uninterrupted variations, shifting the experience of the film to that of listening. The artist borrows an operating principle from music that allows him to expand the framework of representation. Faced with the repetition of visual and sonic motifs, the viewer is invited to experience a subjective temporality that opens the work to different degrees of attention and interpretation. On the pretext of a fictitious event, a studio recording session, Stan Douglas composes, by means of technological devices, the layers of a historical drama replaying the relationships of cultural appropriation induced by a hypermediatized society.