Nobuyoshi Araki

After the presentation of series and bodies of work from the 1970s and 1980s in the new museum’s Ouverture exhibition, the series Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank (1993) by the Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki is presented in Gallery 3 of the Bourse de Commerce.

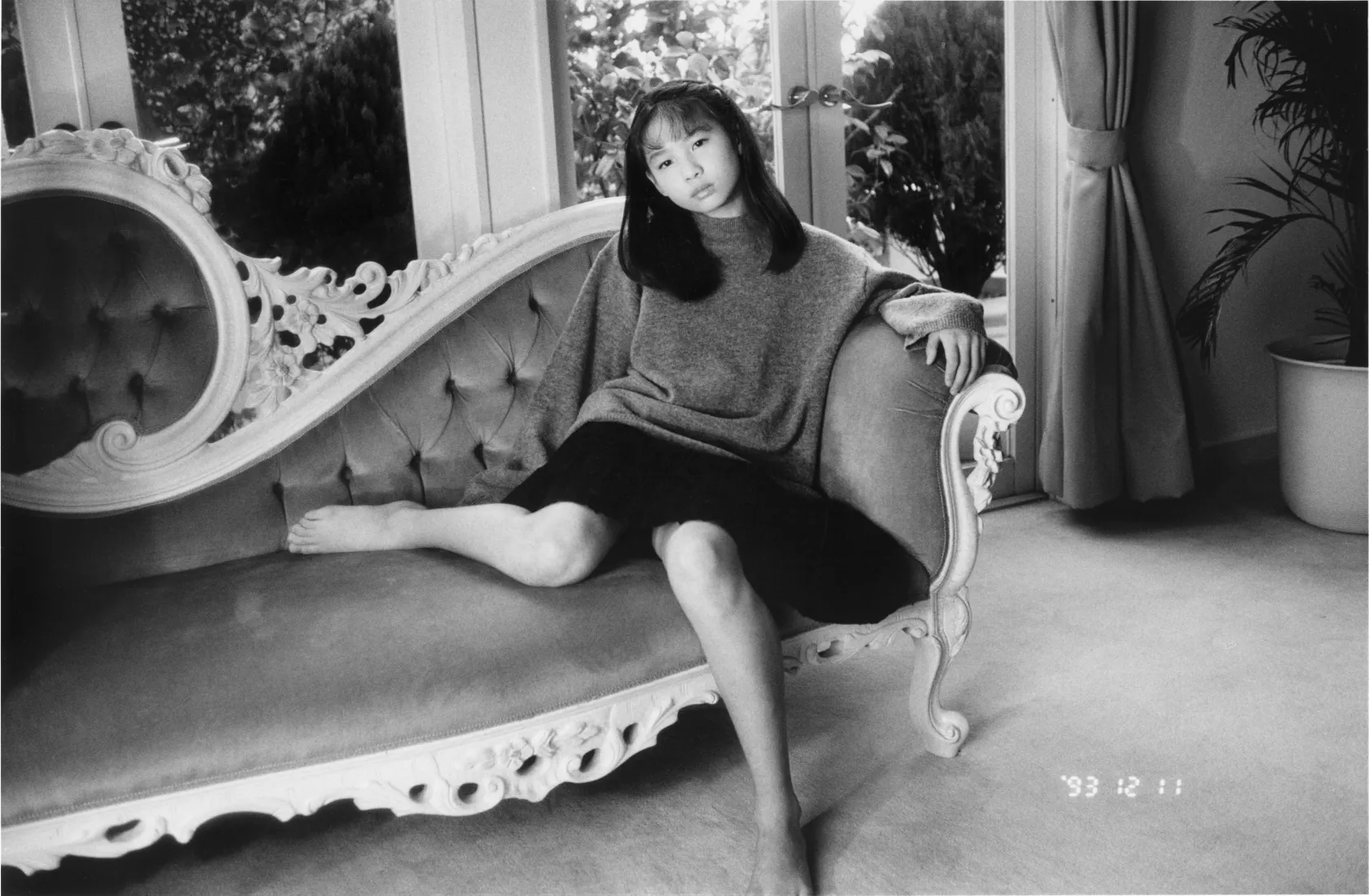

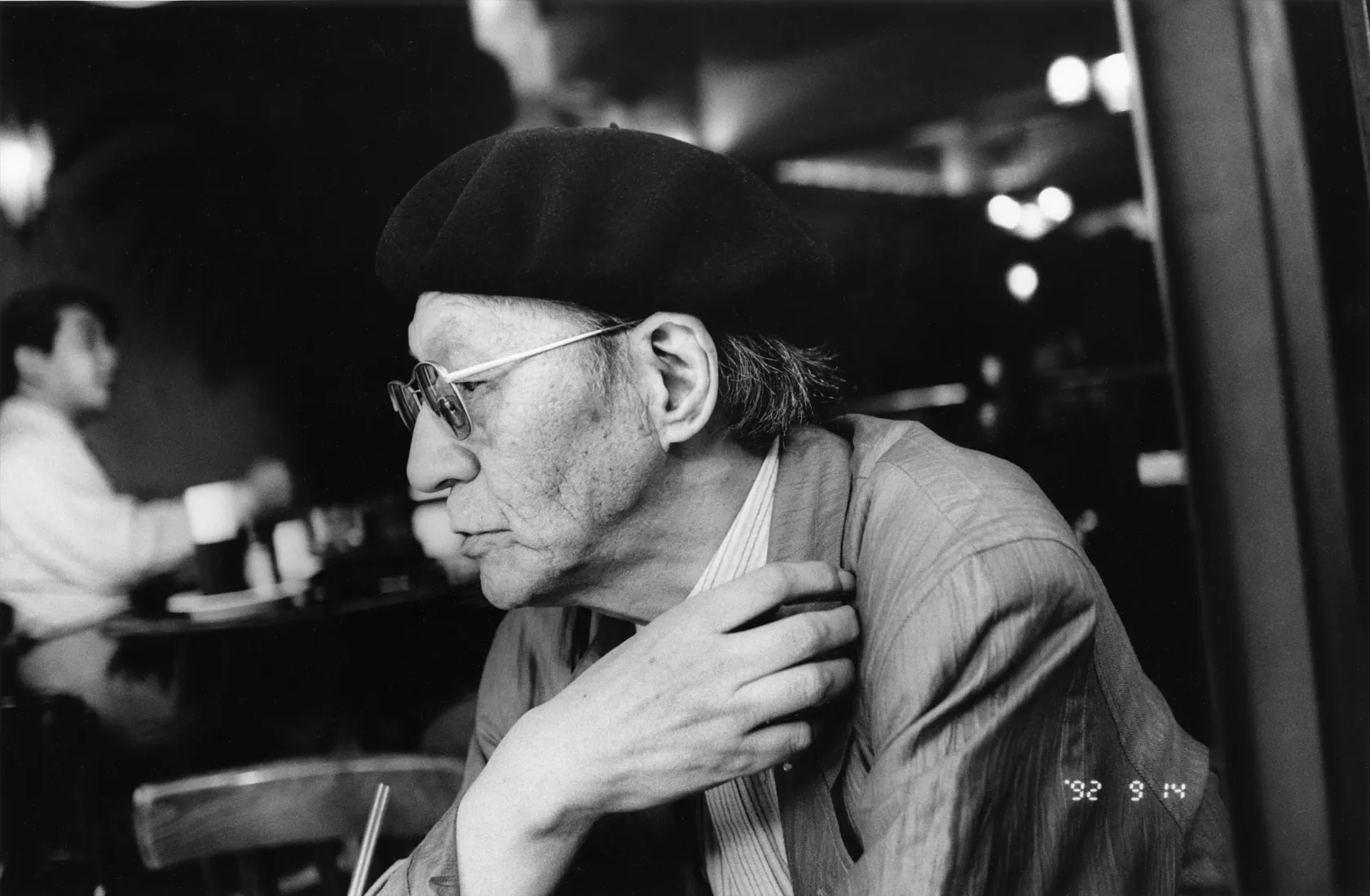

Produced in 1993, three years after the death of his wife Yoko Aoki, this series brings together 101 black-and-white photographs. Whether in the austerity of the studio or the intimacy of the bedroom, the photographer captures his female models in fully frontal poses, explicit and uncompromising, as well as in erotic scenarios. These images are punctuated by photographs of Araki’s new daily life as a widower: still lifes, the streets and skies of Tokyo, the cat, Chiro, he adopted with his wife... Among them, the street photographs echo the work of Robert Frank (1924–2019), a pioneer of American photography, to whom Araki dedicated this series on the occasion of his exhibition at the Yokohama Museum. In this juxtaposition, Araki explores his intimate surroundings and questions both desire and loss.

Araki’s work is known for its direct relationship with reality, which he experiences, lives, and transforms into fiction, so to speak. This approach is very different from that of a reporter, whose supposedly “objective” eye merely observes and records. Araki is not far removed from the generation of Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, or Norman Mailer, who were active in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, and who moved very easily from subjective and personal reportage to fiction and forged what has become known as New Journalism. Araki perhaps goes further by taking his own individuality as his subject. Thus, this photographic mosaic points to the artist’s complex thinking, to the very core of his feelings, impulses, and reflections. Each image, whatever its subject, from the most banal to the most torrid, finds its place in the narrative of his experience of time.

Shi-Nikki [Private Diary] for Robert Frank, also known as 101 Works for Robert Frank, is a collection of 101 photographs dedicated to the iconic author of The Americans, published by Robert Delpire in 1958. As programmatic as it is factual, with a number of images and a dedicatee, the series seems clear, perhaps overly so. Despite these tangible elements, a closer look reveals double meanings and questions. Let’s take a moment to consider the number 101. Often used in sales or marketing, 101 gives the feeling of a generous overflow, a promise of opulence. It is the idea of going beyond the limit, as if the work were opening up to something greater than itself, something unlimited even, with all its associated symbolism, such as infinity or perpetuation. The number 101 can also bring to mind the Bible’s Psalm 101 which is attributed to David and deals with loyalty and lies. The portfolio, made three years after the untimely death of his wife Yoko Aoki, carries this wound, this darkness, which marked a turning point in the artist’s work. Thus, after considering the context in which it was created and the terms of the title, we can ask ourselves about the symmetry of the number 101. A palindromic number, it is composed of two identical units separated by a zero, a possible metaphor for the void imposed by the disappearance of his beloved. Moreover, this symmetry could invoke a face-off with Robert Frank, both as an individual and as the author of The Americans.…

The strength of the series lies in the fact that the narrative is limited to a non-prescriptive suggestion, more emotional than logical, where one figure replaces another, where the bedroom gives way to public spaces, where there is the before and after, life and death. The works dialogue and the themes interconnect: sex, absence, repulsion, the city, infinity. The banal rubs shoulders with the explicit, the eternal, and the ephemeral. This insular immersion into the life of a photographer without his muse is an imaginary journey whose paths cross, lose each other, and invariably lead you back to solitude and emptiness.

Mathieu Humery, curator of the exhibition; Extract from the exhibition catalogue, Bourse de Commerce - Pinault Collection and delpire & co co-edition, Paris, 2021

“A good translator would explain that when Araki says one thing, he is implying at least three others. These early works, which often take the form of diaries or “pseudo-reportages”, immerse us in the world and mind of one of Japan’s most extreme, manic, and creative photographers. What is particularly remarkable about Araki’s entire visual oeuvre, as well as in his writings, and even more so in his long series Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank, is the impression of a free play between the anecdotal or the everyday and the studied pose or composition, between, as it were, his real life and his “artistic life”. Nowhere is this more at stake, more in question, than in his presumably insatiable appetite for photographing the female form, both in situations of presumed intimacy and of extreme and often explicit artifice. Araki, whose heart exploded with love for his wife Yoko to the point of compulsively documenting both the happiness of their honeymoon and the tragedy of her death, is also the photographer immediately associated with images of kinbaku, a traditional and highly ritualized form of Japanese bondage. Western orientalist logic, or external logic, often suggests that this kind of fetishism is inherent in the variable geometry of a seemingly impenetrable Japanese morality: perfectly polite, respectful of convention, and even prudish in public (or during the day), and conversely wildly transgressive in private (or at night). This moral relativism according to which Japanese audiences are more or less shocked by or open to Araki’s work does not, however, help us understand how or why he produces such images. Instead, we should pay attention to the photographs themselves—to their graphic composition, to their intense formal concern, to the narrative (or anti-narrative) logic of the seriality and order in which they appear. Araki incessantly returns to the same scenes, the same subjects and the same places: his neighbourhood, his cat, his collection of plastic dinosaurs, his favourite interiors, his bars, and his models. He once revealed that the first picture he takes every morning is an image of the sky from his balcony: “You brush your teeth, I wash my eyes.”

At first glance, Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank may seem like a deliberately incoherent work, a compilation of all sorts of things and places rather than a homogeneous series, but since it was created by an artist for whom even simple words have slippery meanings, it is perhaps more appropriate here to think of the set of images as another kind of pseudo-journal, a photographic exploration of the spaces between the real and all its potential opposites. In this context, it is useful to recall that it was Araki who coined (in Japanese) the term I-photography, a reference to the so-called I-novels, a Japanese literary genre based on confession that deliberately eliminated any sense of veracity by revealing and admitting things that, in fact, could also be carefully crafted fictions.”

About Shi Nikki (Private Diary) for Robert Frank

Simon Baker, Director of the Maison européenne de la photographie

Nobuyoshi Araki

An engineer by training, Nobuyoshi Araki (born 1940 in Tokyo) became a cameraman and then a photographer. In 1971, he published Sentimental Journey, in which his wedding and honeymoon are revealed in the form of a diary. From the 1980s onwards, Araki increasingly used colour photography to capture flowers and still lifes, prostitutes and Tokyo streetscapes. Araki’s work reveals the changes in Japanese culture through an autobiographical approach, interweaving the themes of eroticism, death, time, and the city. A prolific artist and popular figure in Japan, Araki began his autofictional work very early on, inspiring artists such as Sophie Calle and Roman Opalka.