“Our gaze will give these objects their souls back”—Ali Cherri

Ali Cherri has assembled fragments of objects for the display cases at the Bourse de Commerce, often acquired at auction houses and ignored by history, which he then combines with his own creations.

Your installation is titled 24 ghosts per second. Who are these 24 ghosts?

That was the question I asked myself: which ghosts inhabit this place? In this installation, I tried to imagine bodies and artifacts as if they had lived in and inhabited these spaces. Visitors arrive at a certain point of their history and continue to write this story together with them.

How did your work for the display cases at the Bourse de Commerce come about?

I have been fascinated by these 24 display cases surrounding the Rotunda ever since my first visit to the Bourse de Commerce. This format of the display case, the consummate museum device from colonial museums to the present day, has interested me for a long time. Removed from its original context, the object is framed to exist in a new space. And the number of display cases immediately reminded me of the 24 frames per second that produce the illusion of movement in film. Their circular arrangement encourages you to walk around, clockwise or counterclockwise. This suggests the passage of time. They serve as a kind of freeze-frame, as if we were to take a strip of film and look at just one frame, in the knowledge that something preceded it and that something will follow it.

There is one film in particular that is woven throughout this project. Which one is it?

As a filmmaker and sculptor, the relationship between objects and moving images is central to my thought process. As I was preparing this project for the display cases, I thought about a film that had a huge impact on me, Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet, from 1930. In this film, Cocteau’s thinking focuses entirely on the moving image; we see statues that come to life, objects through the keyhole of a door, and so on. I like this idea of discovering another world hidden behind the one in which we live.

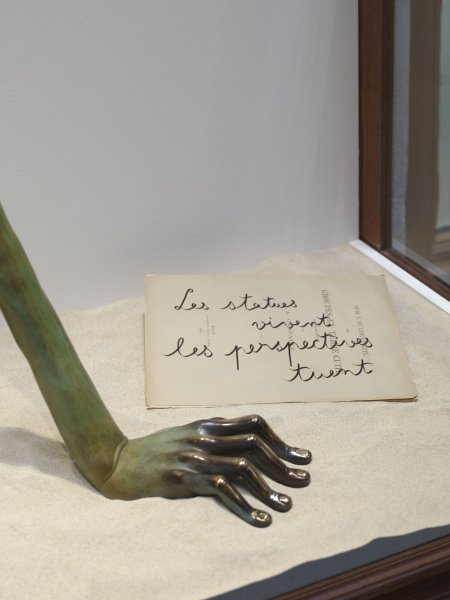

This film became the leitmotif of my narrative. I placed quotes form the movie in some of the display cases, which act as a kind of voice-over that guides the viewer. Some of the sculptures were also directly inspired by this film. A Mouth, A Wound (2025), which depicts two mouths in the palms of two hands, refers to a scene in which a mouth takes shape in the hollow of the poet’s hand, played by Enrique Riveros, and begins to speak.

You mix archaeological finds, fragments of objects, often acquired at auction houses, with your own creations. What is the reason for these combinations?

I create “grafts” in this series of sculptures, a technique I borrowed from botany, which consists of putting two species in contact with one another to create a new one. That’s how I see these fragments of bodies, which come together and cling to each other in an attempt to create new stories, new narratives. They shed the weight of what we have tried to get them to say, and they start a new life through these assemblages. These are bodies that have been shattered by their history, by looting, by a colonial past, and sometimes just by the passage of time. These wounded objects touch me deeply. They have a way of expressing our own human fragility and the way in which, as carriers of often violent histories, we survive these wounds by going towards others and opening ourselves to their pain.

"These games of looking are a way for me to think about the power of the institutions that produce historical narratives and to question the production of these stories."

What role does the gaze play in your practice?

The gaze is central to my work. I have often wondered, especially in a museum space, who is looking at whom? We know that the gaze is subject to a power that conditions our perception, that tells us where to look. I tried to reverse this power relationship in the display cases; we look at the works, but they look at us too. Some open their eyes, while others prefer to keep theirs closed to the violence of the world. These games of looking are a way for me to think about the power of the institutions that produce historical narratives and to question the production of these stories. The gaze is not one-way; it always oscillates between various realities and truths.

Sleep is another topic with which you often grapple.

Today, we are all spectators and witnesses to what is happening in the world. But keeping one’s eyes wide open to all the injustice and violence can be exhausting. Our gaze is already worn down, drained by a consumerist system that bombards us with images, day and night, to the point that we are no longer able to look away. I believe that sleep allows us to undo this state of hyper-vigilance. Rather than a fall – since we talk about falling asleep – I see a rising, a space where we imagine a better world. Returning to the world – when we wake up – is the moment when we give form and body to this dream of a better world.

Your works are being shown as part of the exhibition Corps Et Âmes. What does this theme inspire in you?

Precisely what these objects are trying to say: that they are bodies in search of their souls, which have gone lost, which have been stolen. And our gaze will give them their soul back and breathe life back into them. Just like in a movie. By recording and preserving the traces of bodies, by animating them, by getting them to move and to speak, film awakens the souls of bodies that have remained still.

This installation is presented as part of the “Corps et âmes” exhibition.